Understanding Parkinson's Disease

Parkinson’s disease is a movement disorder that can worsen over time. If you have Parkinson’s, it’s important to know:

- This condition varies widely. No two patients have the same symptoms or rate of progression.

- Symptoms often include poor balance and shaking in the hands, arms, legs or other body parts.

- Parkinson’s is not curable, but it’s also not fatal. You may be able to manage symptoms for years.

- At the same time, Parkinson’s can become disabling. Related conditions can affect quality and length of life.

Find more information and resources for patients and families.

What is Parkinson’s disease?

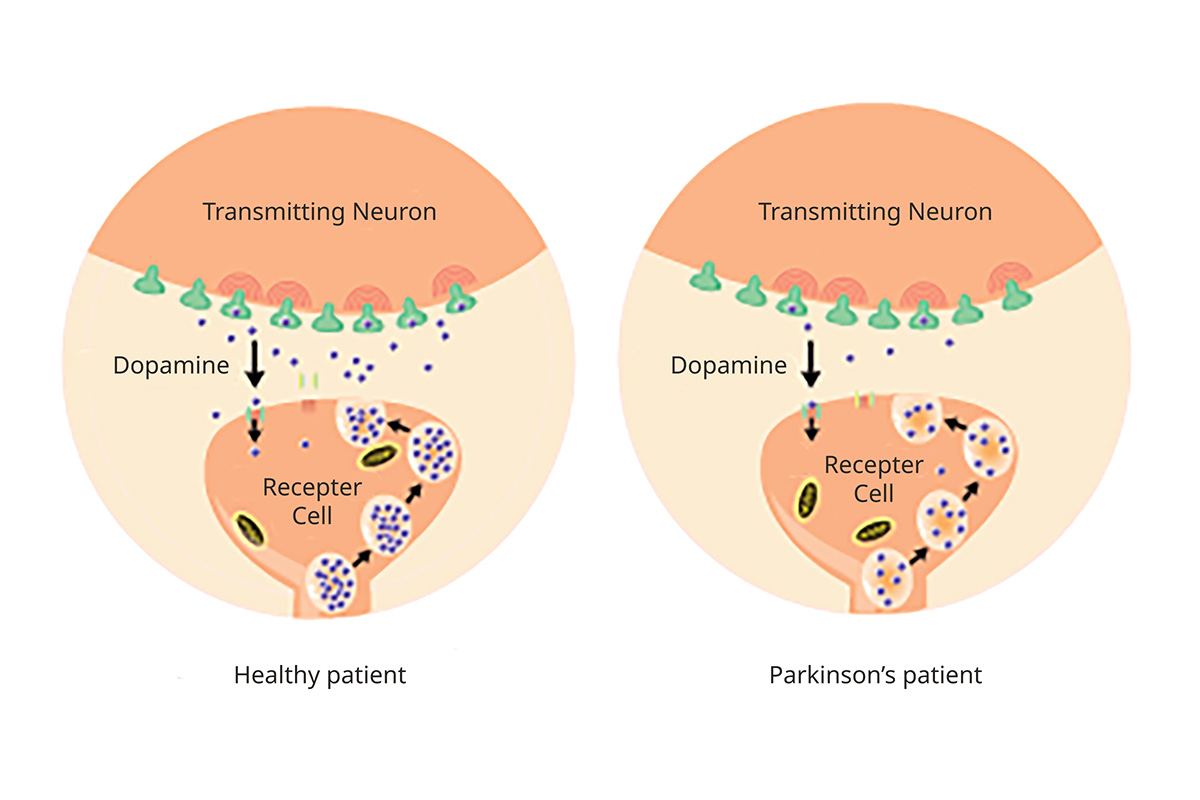

Parkinson’s disease is a disorder of the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) that affects movement. For unknown reasons, brain cells that make a chemical called dopamine die. This leaves the brain without enough dopamine — a “neurotransmitter,” or chemical messenger — to signal nerves to trigger movement.

Parkinson's and Dopamine Production

A progressive illness: Parkinson’s disease is progressive, meaning it worsens over time. It develops quickly in some people, slowly in others. Parkinson’s is also a neurodegenerative disorder because it involves brain cells that die at an increasing rate.

Related disorders: Parkinson’s disease belongs to a group of movement disorders called parkinsonisms. Related conditions include:

- Secondary parkinsonisms

- Parkinson’s-plus, a type of fast-progressing Parkinson’s disease

Who gets Parkinson’s disease?

Estimates vary, but about 1 million people are living with Parkinson’s disease in the U.S. Doctors diagnose about 60,000 cases a year, most in people over age 60. Younger people can also get Parkinson’s. About 5-10% of patients have young-onset Parkinson’s disease, diagnosed before age 50.

About 15% of patients have Parkinson’s-plus syndromes, also known as atypical Parkinson’s. Medications may be less effective for these syndromes, which can lead to disability sooner.

Risk factors for Parkinson’s disease include:

- Age: Risk increases with age. Average age at diagnosis is 65.

- Gender: Men are at higher risk.

- Environmental exposure: Lifetime exposure to well water, which may contain pesticide runoff, can increase risk. So can exposure to air particles containing heavy metals, such as in industrial areas.

- Family history: Having a close relative with the disease could increase your risk. Researchers have identified a dozen genes that may be linked to Parkinson’s disease.

- Sleep disorder: People who act out their dreams are up to 12 times more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease. It’s not clear whether this condition, called REM sleep behavior disorder or RBD, is a cause or symptom of Parkinson’s disease.

- Head trauma: Traumatic brain injury increases risk of Parkinson’s, even years later.

Outcomes

Most doctors don’t consider Parkinson’s fatal because treatments can control symptoms. But related conditions or complications can shorten life. They include:

- Swallowing problems leading to choking.

- Breathing issues such as pneumonia or inability to clear the lungs.

- Lack of balance; this can lead to a fall and broken bones that don’t heal properly.

- Psychosis, requiring antipsychotic medications such as seroquel or clozapine, which are linked to higher mortality rates.

- Dementia, leading to worse quality of life and an increased caregiver burden.

Signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease

About two-thirds of dopamine-producing cells are lost by the time symptoms emerge.

Motor (movement) symptoms

Although motor symptoms are the most noticeable signs of Parkinson’s, they occur later in the disease’s progression. They include:

- Hand tremor; often the first noticeable symptom, affecting about 70% of patients

- Stiff or rigid muscles

- Abnormal muscle tone or movement (dystonia) that starts on one side of the body before moving to the other

- An expressionless face. A person may look disengaged or depressed because muscles don't respond as well.

- Trouble speaking or swallowing

- Smaller handwriting

Nonmotor symptoms

These develop before motor symptoms but are less obvious. The average patient has nine to 12 nonmotor symptoms over the course of the disease, such as:

- Loss of smell

- Constipation

- Sleep problems

- Mood changes, such as anxiety and depression

- Tiredness

- Slower thinking and trouble focusing

- Changes in peeing, such as having to go right away or more often

Screening

There is no screening for Parkinson’s disease. To view the region of the brain where dopamine-making cells die, OHSU researchers at our Neuroimaging Laboratory use the most advanced MRI available. They want to understand cell death better so they can potentially find Parkinson’s earlier.

Types of parkinsonism

Parkinsonism, the umbrella group of diseases that includes Parkinson’s, has several categories:

Primary Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease accounts for 80% of parkinsonisms. It’s also called primary parkinsonism.

It is idiopathic, meaning it has no known cause. The brain commonly contains misshapen or undigested proteins called Lewy bodies, but their role is unknown.

Parkinson’s responds to a medication called levodopa, which the body converts into dopamine to keep muscles working.

Secondary parkinsonism

Symptoms are like those of Parkinson’s disease but have a known cause such as:

- Antipsychotic medications such as haloperidol or risperidone. Stopping them often improves symptoms.

- Vascular parkinsonism, caused by cerebrovascular risk factors such as diabetes, high cholesterol, smoking and lack of exercise. Levodopa is less effective for this type.

- Infections such as encephalitis.

- Exposure to toxins such as carbon monoxide and mercury.

Parkinson’s-plus

These conditions, also called atypical parkinsonism, can be difficult to distinguish from primary parkinsonism in early stages. Patients do not respond well to levodopa, or levodopa helps only briefly. Types include:

Progressive supranuclear palsy: Patients have problems with balance and eye movement.

Multiple system atrophy (MSA): Patients have trouble with balance and the nervous system that controls automatic functions such as breathing, blood pressure and digestion. Patients may have symptoms such as low blood pressure, with dizziness and lightheadedness. They may also have impotence, and severe constipation and urinary changes.

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD): These patients may have a combination of parkinsonism symptoms. In addition, they may hold an arm in an odd position and may have a jerky tremor.

Dementia with Lewy bodies: This parkinsonism worsens over time. It occurs when proteins called Lewy bodies build up in the part of the brain that controls behavior and movement. Patients with standard Parkinson’s may have Lewy bodies, but it doesn’t mean they’ll develop dementia.

Read more about these and other movement disorders.

Stages

Because Parkinson’s varies so much by patient, specialists use stages to track its progress. The most common measurement, called the Hoehn and Yahr scale, starts when symptoms appear:

- Stage 1: Symptoms are mild and limited to one side of the body. The patient may have no physical impairment.

- Stage 2: Symptoms are mild but on both sides of the body.

- Stage 3: Symptoms are moderate. Movements are slower. Loss of balance makes falls more common. People can still live alone.

- Stage 4: People need help with daily activities and can no longer live alone.

- Stage 5: Patients are bedbound or unable to walk, requiring around-the-clock care.

It’s important to remember that every patient experiences Parkinson’s differently. Some people live with Parkinson’s for 20 years or more, and some never progress to later stages. Patients do best by working closely with a care team that can design a custom treatment plan.

For patients

- Referral: To become a patient, please ask your doctor for a referral.

- Questions: For questions or follow-up appointments, call 503-494-7772 .

- Find forms for new and returning patients.

Location

Parking is free for patients and their visitors.

OHSU Parkinson Center

Center for Health & Healing Building 1, eighth floor

3303 S. Bond Ave.

Portland, OR 97239

Map and directions

Refer a patient

- Refer your patient to OHSU.

- Call 503-494-4567 to seek provider-to-provider advice.

Patient resources

Email pcoeducation@ohsu.edu to sign up for our newsletter.