Ateriovenous Malformation (AVM) and Other Cerebrovascular Disorders

We offer you the most advanced care for AVMs and other cerebrovascular (blood vessels inside the head) conditions. Experts from the OHSU Brain Institute and the Charles T. Dotter Department of Interventional Radiology work to together to provide:

- The most advanced imaging options.

- Treatment with specialists trained in both neurosurgery and neurointervention (treatment within blood vessels in the brain and spine).

- Expert neurosurgeons who are among the few in the U.S. who do bypass surgery for rare stroke conditions such as moyamoya disease.

- Team-based care with treatment tailored to every type of malformation.

- Care in a leading center with many patients and excellent outcomes.

Understanding AVMs

What is an AVM?

An AVM is a cluster of abnormal blood vessels found on or in the brain. Rarely, they form in or near the spinal cord. An AVM has three parts:

- Feeding arteries that carry high-pressure blood from the heart.

- Draining veins that carry low-pressure blood back to the heart.

- A central core of tangled vessels called the nidus. In this tangle, arteries are directly connected to veins. Normally, they are connected through small blood vessels called capillaries.

How do AVMs cause problems?

Nutrients: Normally, blood moves from arteries to veins through a network of capillaries. The capillaries distribute the blood, with essential oxygen and nutrients, to brain tissue. When they’re absent, brain tissue may be deprived.

Blood flow: Capillaries dramatically slow blood flow. When high-pressure blood flows from arteries directly to veins, the veins can eventually stretch and rupture.

Pressure: AVMs can press on or displace delicate brain tissue.

What causes AVMs?

It’s unclear. AVMs are present at birth but rarely hereditary (passed down in families). They occasionally form after head trauma.

Who gets AVMs?

Brain AVMs are rare, occurring in less than 1% of the U.S. population. They may be slightly more common in men than women.

Signs and symptoms of an AVM

Some AVMs never cause symptoms and may never be diagnosed. Others may cause a range of symptoms depending on their location in the brain. Symptoms can include:

- Seizures

- Headache or pain in one area of the head

- Muscle weakness or numbness in one part of the body

- Problems with speech, vision or movement

- Memory deficits

- Developmental delays

- Confusion or hallucinations

In some people, a rupture with bleeding in the brain is the first sign of an AVM. Symptoms of a hemorrhage (bleeding) may include:

- Headache

- Seizures

- Difficulty speaking or understanding speech

- Coma

Screening and diagnosis

There is no routine screening for symptomless, unruptured AVMs. Many AVMs are discovered only after a scan done for another reason. Screening scans may be recommended for people with a history of AVM.

Computed tomography or CT scan: This uses X-rays from many angles to produce cross-sectional images of the brain. If symptoms suggest that an AVM has ruptured, it’s a quick way to see any bleeding in the brain.

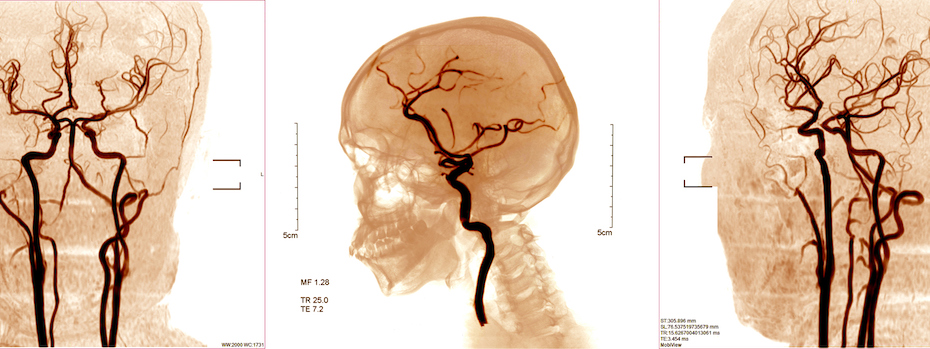

Angiograms: These tests show detailed images of blood vessels and blood flow in the brain. They are used to find AVMs, and to see their size and shape.

- CT angiogram (CTA): This takes 3D X-rays, often after an injection of dye to highlight blood vessels.

- An MR angiogram (MRA): This uses magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed computer images of the brain. This imaging can be done with or without dye.

- Cerebral angiogram: A cerebral angiogram uses advanced X-ray imaging to guide a catheter (thin plastic tube) through a leg artery to the brain. A dye highlights blood vessels and blood flow so doctors can see the size, shape and location of an AVM. Your care team can also use the catheter to insert tiny tools to treat the AVM.

Treatments

Treatment depends on factors including:

- The AVM’s size

- The AVM’s traits

- The AVM’s location in the brain

- Your age and general health

The goal of AVM treatment is to prevent new or recurring bleeding. Eliminating the AVM with surgery, radiation, embolization or a combination offers the best outcome.

Surgical removal: The neurosurgeon temporarily removes part of the skull to reach the brain. Using a surgical microscope, the surgeon clips and seals all the blood vessels feeding and draining the AVM, then removes the nidus.

Stereotactic radiosurgery: Highly focused radiation beams are aimed at the AVM. This sets off a scarring process that causes blood vessels to seal and shrink over one to three years. This treatment may be recommended for smaller AVMs.

Endovascular embolization: This endovascular (inside the blood vessel) treatment is often done before surgery. A doctor navigates a catheter through blood vessels to the AVM. The doctor packs the feeding and draining vessels with an embolizing (blocking) material such as tiny coils or a gluelike substance. This seals the vessels and reduces blood flow to the AVM, making it smaller and less likely to bleed during surgery.

Other cerebrovascular disorders

Cavernous malformations are abnormal clusters of small blood vessels with pockets or “caverns” of slow-flowing blood. This disorder has several subtypes, including some that run in families. They are also called cavernomas or cavernous angiomas.

They generally pose less risk than AVMs but can sometimes bleed and cause seizures. Surgical removal is sometimes recommended.

Our specialists customize treatment for every fistula, a type of abnormal blood vessel connection. Therapies include embolization, flow diversion and surgery.

Dural arteriovenous fistulas: These rare malformations are named for their location in the dura, the brain’s leathery covering. As in an AVM, arteries and veins are connected without capillaries that slow blood flow. This can sometimes lead to bleeding or stroke. These are also called dural fistulas and dural AVM.

Carotid-cavernous fistulas: These fistulas involve an abnormal connection between the carotid artery in the neck and a large vein behind the eye.

In this rare progressive stroke disorder, first described in Japan, narrowed arteries at the base of the brain restrict blood supply. Very small abnormal blood vessels form to compensate, making a pattern that looks like a puff of smoke — moyamoya in Japanese. The main symptoms are recurring strokes or transient ischemic attacks (TIA or mini stroke).

Expert neurosurgeons from OHSU are among the few in the United States who regularly perform bypass surgery for moyamoya disease and other rare stroke conditions.

This type of abnormal vein is present at birth and rarely bleeds. Venous angiomas are usually left untreated. A venous angioma may be:

- An abnormally wide vein.

- A cluster of wide veins arranged like the spokes of a wheel.

- A vein that appears in an abnormal spot in the brain.

Learn more

- Arteriovenous Malformation Information Page, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- Arteriovenous Malformations and Other Vascular Lesions of the Central Nervous System Fact Sheet, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- Moyamoya Disease Information Page, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- Cerebral Cavernous Malformation Information Page, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- Vascular Malformations of the Brain, National Organization for Rare Disorders

For patients

- Call 911 now if you or someone else may be having a stroke. Learn the BE FAST signs of stroke.

- Referral: To become a patient, please ask your doctor for a referral.

- Questions: For questions or follow-up appointments, call 503-494-7772 .

Location

Parking is free for patients and their visitors.

OHSU Stroke Program clinic

Hatfield Research Center, 13th floor

3250 S.W. Sam Jackson Park Road

Portland, OR 97239

Map and directions

Refer a patient

- Refer your patient to OHSU.

- Call 503-494-4567 to seek provider-to-provider advice.

- Find OHSU’s stroke practice standards on our For Health Care Professionals page.

Patient resources

- Find resources for patients and families.

- Learn about stroke prevention.

- Learn how our Telemedicine Network can bring OHSU expertise to your community.