One hundred years ago, average life expectancy in the U.S. was about 60, and the most common cause of vision loss was cataracts. No one was particularly worried about losing their sight from age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which tends to manifest itself in people over 50. Now that average life expectancy is roughly 76 and rising, it’s more common for people to lose vision from AMD—and potentially live for 20 or more years. This phenomenon is not confined to the U.S. As the world population ages, and life-expectancy increases, AMD is expected to become even more common, with the number of estimated cases worldwide predicted to reach 288 million by 2040.

“That’s why it’s so important to improve early detection and develop new treatments,” said David Wilson, M.D., Paul H. Casey chair and director of Casey Eye Institute. “People are living with poor vision for many years, and it makes a big impact on their quality of life.”

Casey has been at the forefront of AMD research and care for decades, creating increasingly better tools to diagnose and treat AMD. The new Wold Family Macular Degeneration Center is a central hub for the many research and clinical care efforts already underway, and a catalyst for further discovery and innovation by having research, clinical care and clinical trials all in one place. Indeed, Casey is involved in more macular degeneration clinical trials than almost anywhere in the world.

What we do and don’t know about AMD

There are two kinds of AMD. Wet AMD is less common but a more immediate threat to vision. It’s caused by the growth of abnormal blood vessels in the retina. The other, called dry AMD, develops when the cells in the retina start to atrophy. Dry AMD is more common and progresses more slowly.

There are effective treatments for wet AMD, but there is still no way to stop vision loss caused by dry AMD.

“We don’t have a complete understanding of what causes AMD, but we do know some of the molecular mechanisms associated with disease progression. For wet AMD, a key molecule called vascular endothelial growth factor was identified and an effective treatment was developed by blocking its action. For dry AMD, we don’t have the key to treatment yet, but an active search is underway,” said David Huang, M.D., Ph.D., Peterson Professor of Ophthalmology and Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Associate Director of Casey Eye Institute.

Less time in the clinic for wet AMD patients

The Wold Family Macular Degeneration Center was a crucial clinical trial site for two promising treatments for wet AMD that gained FDA approval in the last year. As with all newly FDA-approved treatments, Casey will wait at least six months before offering the new treatments to patients.

One treatment, now known as Suvismo™ (ranibizumab), takes the form of a permanent, reusable drug reservoir that allows wet AMD patients to forego monthly eye injections. The second, Vabysmo® (farcimab-svoa), is an antibody drug administered every four weeks for the first four doses, after which patients can potentially scale back to twice a year.

Both treatments have the potential to not only slow the progression of wet AMD, but to also improve patients’ quality of life.

New hope for dry AMD patients

Historically, advanced dry AMD has been harder to treat than wet AMD, but new research could change that. One of the current clinical trials at the Wold Family Macular Degeneration Center is the Gallego study, which is testing a promising new drug designed to preserve retinal integrity and slow disease progression.

Another investigational treatment builds on Casey’s experience as a national leader in gene therapy for retinal diseases. Casey is one of the sites conducting an international gene therapy study involving surgical treatment for dry AMD. The study entails a procedure in which surgeons replace or augment a gene associated with dry AMD.

In patients with AMD, the cells in the retina start to degenerate and disappear. A research team at Casey is exploring cell-based therapy to restore function, by transplanting cells back into the retina. The research is still in its early stages, but there is reason to be optimistic about this cutting-edge treatment.

Advanced imaging improves diagnosis and treatment

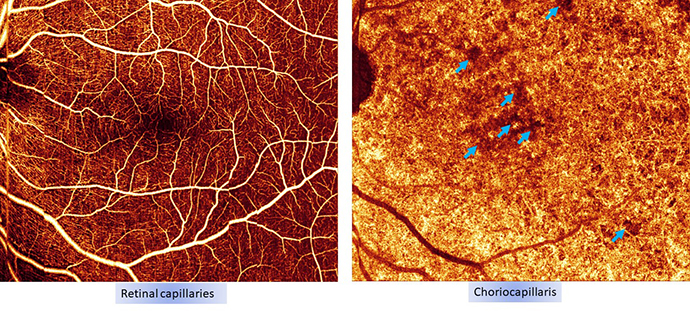

Long heralded as leaders in ophthalmic imaging, Casey is constantly improving its ability to visualize and track changes in areas of the eye affected by AMD. Today’s primary tools for detecting AMD are optical coherence tomography (OCT) and OCT angiography, areas where Casey researchers are at the forefront of innovation.

“With OCT angiography, we can detect the onset and progression of wet AMD before fluid leakage occurs. For dry AMD we can visualize the degeneration of the layers in the retina, before vision is affected,” said Dr. Huang. “Detecting changes in these layers is key to early diagnosis as well as assessing the effectiveness of potential new drugs to treat dry AMD.”

Slow and steady progress

Progress can be slow and painstaking, but today’s AMD patients have much better options than they did only 20 years ago.

“I have patients who were in the original studies when I started here, close to 20 years ago, who are still able to see. So that’s amazing progress. We have treatment options now that mean people don’t have to worry about going completely blind, at least with the wet form of AMD. As long as they can get the injections and can come in, they are often able to maintain their vision, which is amazing,” said Christina Flaxel, M.D., Bula Buck Arveson and Charles C. Arveson Professor of Macular Degeneration Research and director of the Wold Family Macular Degeneration Center.

This holds true for dozens of other eye conditions, and underlines the importance of basic science and clinical trials. One small research breakthrough leads to another and, eventually, a meaningful new option for patients.

A personal commitment

Philanthropist John Wold developed macular degeneration in his early 80s and lived with declining vision until his death at 100. “He had two decades in which his independence was quite limited. He knew first-hand how serious AMD could be,” said Dr. Wilson. “His generosity, and that of The Wold Foundation, established the Wold Family Macular Degeneration Center that is making it possible for us to speed progress toward a cure.”