Central Oregon

Kaitlin Greene - OHSU Community Research Liaison

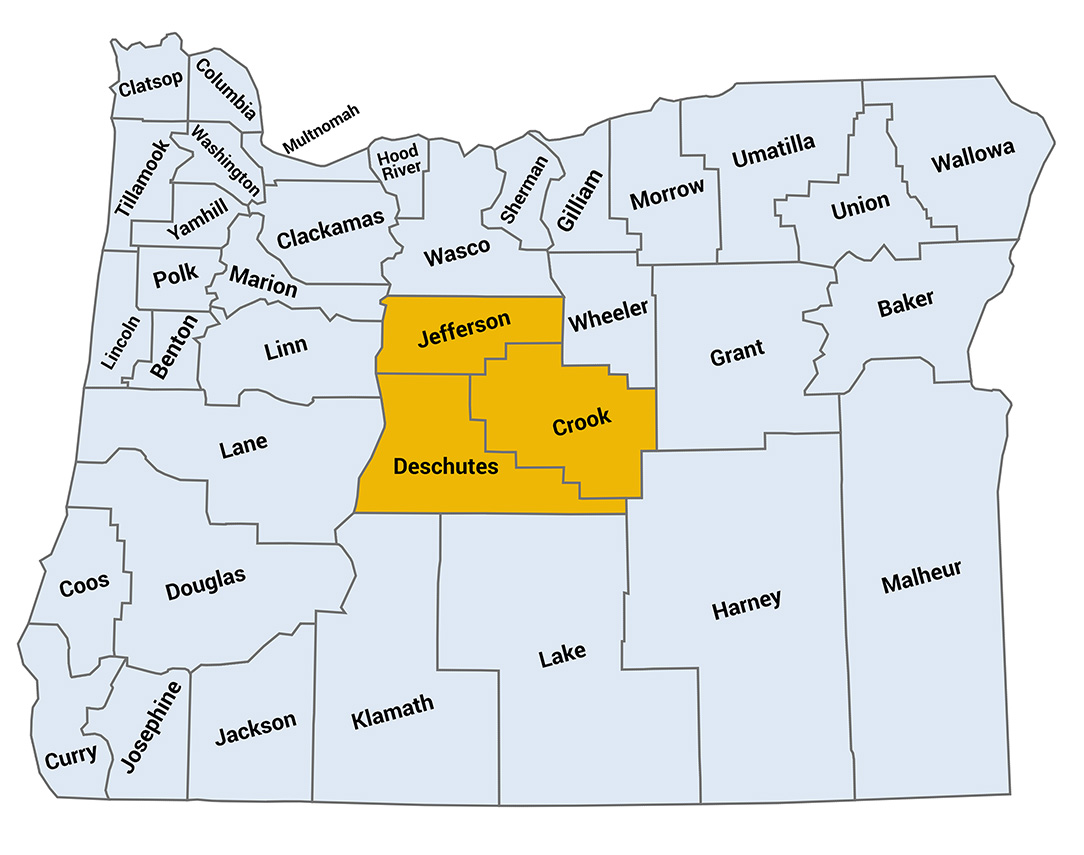

Kaitlin is located in the Hub office in Central Oregon and her region includes Deschutes, Crook, and Jefferson counties.

If you would like to contact Kaitlin, please email greenkai@ohsu.edu

Kaitlin's role on the Community Engaged Research Team:

- Building relationships and identifying opportunities for collaboration to support their community in implementing research best practices and evidence-based approaches.

- When opportunities are identified, collaborative projects are initiated through the Project Assistance Program or the Central Oregon Research Coalition.

- Support OHSU academic collaborators by engaging stakeholders and community members. Provide county level data and knowledge about the region, facilitate partnerships and projects and data collection (e.g. focus groups, interviews, surveys)

Central Oregon Research Coalition (CORC)

CORC is a community-university collaborative, coordinated by the Central Oregon Community Research Liaison and led by a community Steering Committee. The CORC Steering Committee selects projects to work on that advance our mission of connecting Central Oregonians to strengthen data-driven decision making and research-based practices to improve health and wellbeing. CORC also hosts Community Education and Networking events that provide an opportunity for community members to learn about research and data and connect with those who are doing related work.

Mission: Connecting Central Oregonians to strengthen data-driven decision making and research-based practices to improve health and wellbeing

Vision: Communities use data and research to inform decisions for a healthy and thriving Central Oregon

Quarterly events include a short presentation on a topic related to data and/or research and time for networking. Events create opportunities to strengthen data-driven decision making and research-based practices in Central Oregon and are held at rotating locations throughout Central Oregon. For more information sign up for our email list here.

The CORC Steering Committee selects community projects to support that advance the CORC mission. The first project was a collaboration with the Homeless Leadership Coalition to expand on their data collection processes and data analyses for the annual Point-In-Time Count. CORC is currently collaborating with the Center for Age-Friendly Excellence on preparing Central Oregon towns to receive World Health Organization recognition as Age-Friendly. The Steering Committee is also creating a community-training program to increase the capacity of local organizations to use data and research-best practices.

If you are interested in joining the CORC Steering Committee contact Laura Campbell for more information.

CORC’s first project was a collaboration with the Homeless Leadership Coalition to expand on their data collection processes and data analyses for the annual Point-In-Time Count. CORC is currently collaborating with the Center for Age-Friendly Excellence on preparing Central Oregon towns to receive World Health Organization recognition as Age-Friendly. CORC is also creating a community-training program to increase the capacity of local organizations to use data and research-best practices.

Project Assistance Partnerships

The Community Research Hub consults on and manages select projects through the Project Assistance Program. Review current partnerships below.

- In collaboration with the Latino Community Association and the OHSU Evaluation Core: Evaluation of an after-school program designed in improve educational outcomes, cultural pride, and Spanish literacy.

- In collaboration with TRACEs Central Oregon: Measurement of Central Oregonian’s knowledge and awareness of trauma and resilience by designing a survey, collecting and analyzing data, and communicating results back to the community. Key stakeholder interviews to assess Central Oregon’s readiness to take action to build resilience in communities.

- In collaboration with the Early Learning Hub of Central Oregon, the Jefferson County of Public Health, and Northwestern University Mothers & Babies Program: Regional training, implementation, and evaluation of an evidence-based intervention to prevent postpartum depression.

- In collaboration with Deschutes County Health Services and the OHSU Evaluation Core: Implementation and evaluation planning for the DCHS Crisis Stabilization Center.

Project snapshot

Age Friendly Central Oregon

Age-Friendly is a World Health Organization (WHO) initiative encouraging active aging by optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security across sectors to enhance quality of life of older adults. By working towards age-friendly recognition Central Oregon towns, starting with Bend and Prineville, become part of a global network of 705 cities and communities in 39 countries who are committed to listening to the needs of their ageing population, assessing and monitoring their age-friendliness, and working collaboratively with older people and across sectors to create age-friendly physical and social environments. By being part of this network, Central Oregon towns also gain access to a wealth of resources on how to create age-friendly environments and therefore improving health outcomes for older adults.

- The Center for Age-Friendly Excellence

- Central Oregon Research Coalition

- Laura Campbell, OHSU Community Research Liaison

- Katie Hernandez, Community Research Intern

As CAFE was establishing a presence in Central Oregon, they came to CORC because of our strong community ties and research skills to collaborate on improving the physical and social environments for older adults. The first step in this initiative was assessing the current environment to identify strengths and areas for improvement that will contribute to the community becoming more age-friendly.

We accomplished this by collating recent data sources, such as needs assessments and surveys, which cover the 8 Age-Friendly domains of Outdoor Spaces, Transportation, Housing, Social Participation, Social Isolation, Civic Participation and Employment, Communication and Information, and Community and Health Services. We identified data and information via online searches and leveraging CORC Steering Committee members’ and invested community partners’ existing knowledge and relationships. Data sources consisted of reports as well as two raw data sets that were analyzed. Data were organized by the 8 Age-Friendly Domains and into one report for each of the three counties (Crook, Deschutes, and Jefferson) providing a baseline picture of strengths and gaps in each domain.

Older adults are the fastest growing demographic in the United States. Ten thousand persons turn age 65 in the United States every day and this trend will continue until about 2030. According to the Population Research Center at Portland State University, Bend, Oregon is now the fastest growing city in the West and much of that trend is fueled by in-migration of baby boomers with significant economic resources and health needs. According to the U.S. Census, Central Oregon’s population of older adults aged 65-plus increased by 58% between 2010 and 2016, which is twice the growth of all of Oregon. Currently, Deschutes County has a 65-plus population of 34,992, up 49% since the 2010 census, followed by Crook at 5,575 (up 33%), and Jefferson at 4,316 (up 30%). The growth is dramatic.

Local gerontologists and aging services professionals forecast startling trends that highlight critical needs:

- Older persons will significantly increase in population;

- mounting numbers of older adults will struggle with chronic physical and neurological disorders;

- physicians who accept Medicare as payment are rare and sometimes nonexistent;

- caregivers will be stressed and in need of assistance themselves;

- barring intervention, government assistance for the aged will diminish;

- affordable housing is urgently needed;

- there is a growing income disparity between older adults;

- isolation and loneliness are demonstrated health risks and lack of transportation is a key;

- it is becoming more difficult to hire qualified professional caregivers for dependent older persons.

It is vital for Central Oregon to prepare for the aging population’s health needs and develop a regional strategy for integrated programs and services that are evidence-based and coordinate with local jurisdictions. By working towards Age-Friendly recognition, health outcomes for older adults will improve and additional resources will be available to the community.

CAFE has strong experience working with communities to become Age-Friendly yet because the organization was new to Central Oregon they did not have the community connections to know whether this would be a priority here or how to implement effectively if it was. Because the CORC Steering Committee is made up of key public health stakeholders they were able to advise that becoming Age-Friendly was indeed a high priority. In addition, the community leaders who are part of the CORC Steering Committee we were able to leverage their roles and relationships to identify data sources and key stakeholders for the baseline assessment in an in-depth and comprehensive way that would not have been possible otherwise.

The research lens that the Community Research Hub brought to the project added value by identifying long-term outcome measurement strategies and performing tailored data analyses, which CAFE had not previously done when working with other communities.

Some findings were consistent across counties:

- Lack of current information about the attitudes of older adults about community resources

- Very few 65+ adults utilize public transportation

- Little information exists about Social Participation and Communication needs of older adults in the community

For Bend and Crook County:

- Social Isolation among older adults remains a prominent problem (as corroborated by the high rates of mental health disorders)

In Bend:

- About 65% of older adults in Bend are rent or mortgage burdened (spend more than 30% of monthly income on housing)

In Crook County:

- Developing a built environment that optimizes physical activity such as walking and biking is a top priority of Crook County residents

Next Steps

Additional primary data collection is needed to fill gaps in existing information about the 8 Age-Friendly domains in the region. CAFE, OHSU Community Research Hub, Council on Aging, and St. Charles co-hosted a Regional Age-Friendly Summit. At the Summit break out groups of experts, key stakeholders, and community members used the reports we developed as a starting point to discuss each of the domains and identified areas of need and next steps. CAFE and OHSU will then conduct focus groups with older adults and providers who work with older adults to collect additional baseline data. Information from the secondary data reports, the Regional Age-Friendly Summit, and the focus groups will be triangulated to develop recommendations for becoming Age-Friendly.