A Successful Design

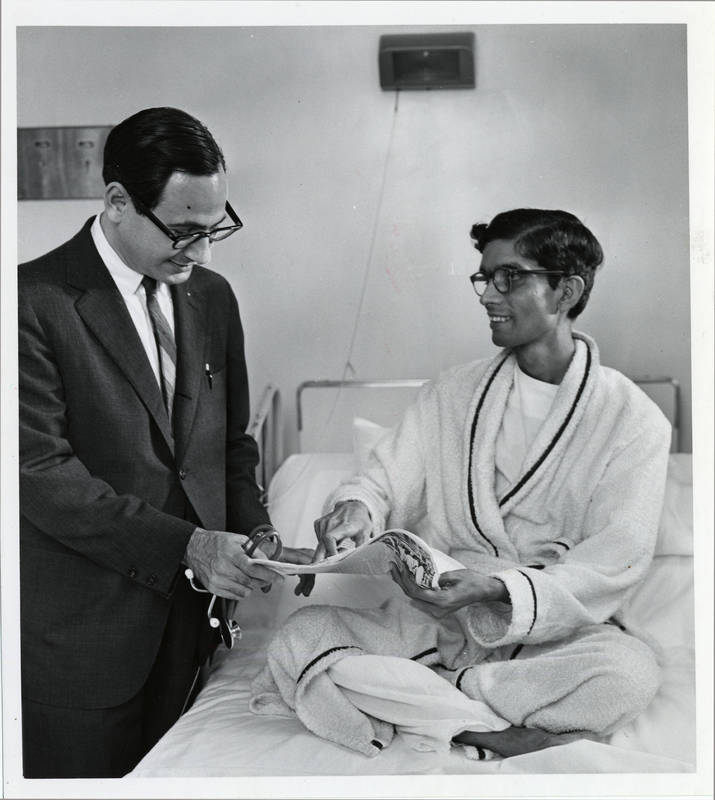

In 1960, Herbert Griswold, MD, the chief of cardiology at University of Oregon Hospital, learned of the durable function in dogs with a ball-in-cage mitral valve prosthesis. Griswold referred to Starr for valve replacement surgery a young woman near death from a severely damaged mitral valve. In August of 1960, Starr replaced her damaged mitral valve with a prosthesis Edwards had fabricated in his workshop. Her post-operative cardiac function was excellent, but she suddenly died 11 hours after surgery when air trapped in her enormously dilated left atrium embolized to her brain. This devastating outcome disheartened but did not discourage Starr and Edwards. Starr had learned a painful but vital technical lesson. Nonetheless, Starr and Edwards were encouraged by the valve’s performance. Four weeks later, Starr inserted a mitral valve prosthesis into a second patient. That man’s spectacular recovery and return to a normal life was dramatic proof that the prosthesis was effective and durable.

On March 21, 1961, Starr and Edwards presented the results of their first eight patients to the prestigious American Surgical Association. Five patients with terminal heart failure returned to normal lives after insertion of the Starr Edwards valve. The manuscript published a few months later would be one of the top 100 medical manuscripts published in the 20th century:

Meeting the Demand

By 1961, Edwards concluded that clinical success with the mitral valve obligated him to establish a business that would produce high-quality cardiac valve prostheses. Edwards founded and incorporated Edwards Laboratory, convincing an old trusted friend, Ray Astle, to join him as the general manager. They rented space in a small building in Santa Ana, California, and with two employees began to manufacture Starr-Edwards mitral valve prostheses one at a time.

Demand for the valves rapidly increased in 1962 and 1963. Edwards and colleagues confronted major problems when trying to achieve reliable production. These were overcome through persistence and unswerving commitment to produce the highest quality valves.

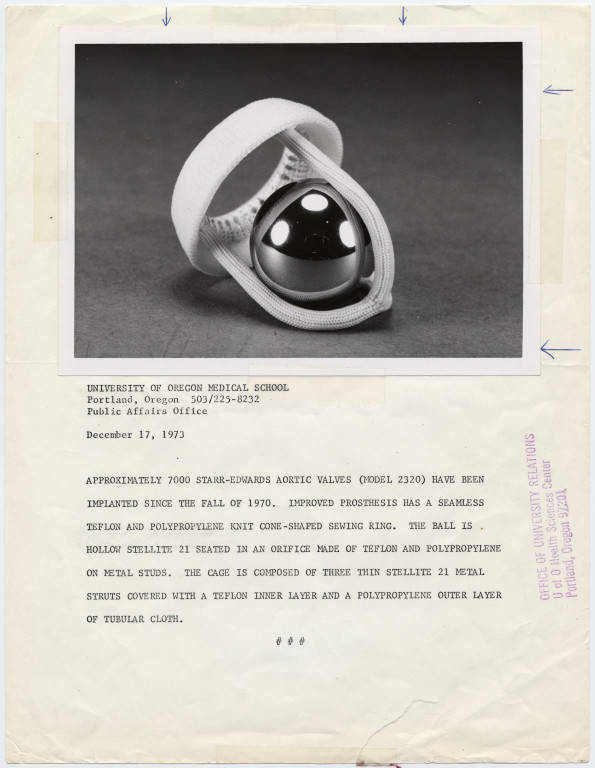

In 1961, after their success with the mitral valve prosthesis, Edwards and Starr turned their attention to inventing a ball-in-cage prosthesis to replace the aortic valve. The function and anatomy of the aortic valve are substantially different from the mitral valve, and thus modifications to the original design were required. The four struts were replaced by three struts of reduced thickness, made of an exceptionally hard alloy, Stellite 21. The sewing ring had to be shaped to conform tightly to the high-pressure flows across the aortic valve. Edwards refined the structure of the aortic valve in incremental steps, attempting to achieve maximum performance. In 1963, Starr and Edwards reported their clinical experience with aortic valve replacement with what they termed their “semi-rigid ball-valve prosthesis.”