Congenital Heart Defects in Children

OHSU and Doernbecher Children’s Hospital offer lifelong care for children born with a heart problem. You’ll find advanced therapies and a team of experts for any defect, from simple to complex.

We offer:

- Fetal and children’s heart specialists who are available 24/7.

- Advanced tools to diagnose and treat heart defects before birth or in infancy.

- Noninvasive and minimally invasive techniques, such as catheterization, to avoid surgery for your child whenever possible.

- Lifelong care, with a seamless transition to OHSU’s adult congenital heart disease program, the only one in Oregon and southwest Washington.

Find links to more information about congenital heart defects on our Resources for Patients and Families page.

Understanding congenital heart conditions

What are congenital heart defects?

Congenital heart defects are problems with the heart’s structure that are present at birth. They develop during the first eight weeks of pregnancy, when the heart is formed. A defect can happen when development takes a wrong turn somewhere along the way.

Most defects are simple, and many don’t require treatment. Some are more complex and may need to be treated with one or more surgeries over years. Most treated children go on to lead normal lives.

Who gets congenital heart defects?

Congenital heart defects are among the most common type of birth defect. At least eight in 1,000 babies are born with a heart defect in the U.S. each year.

Some heart problems run in families or are linked to genetic syndromes, such as Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome). Most of the time, though, doctors don’t know the exact cause. There is nothing parents did or didn’t do to cause their baby’s heart disease.

Symptoms of congenital heart defects

Symptoms most often appear soon after birth. They may include:

- Blue lips, skin, fingers and toes

- Poor blood circulation

- Pale or ashen skin

- Rapid breathing or breathlessness

- Difficulty feeding

- Poor weight gain

- Lung infections

Sometimes, symptoms appear later in childhood or in adulthood. These can include:

- Dizziness

- Trouble breathing

- Fainting

- Fatigue

- Less ability to play or exercise

Diagnosing congenital heart defects

Almost all newborns in the United States are screened for congenital heart defects. Doctors also find heart defects before birth during fetal ultrasounds.

Doernbecher has the largest fetal heart care program between Seattle and San Francisco. Our experienced team is more likely to find, and in some cases treat, congenital heart conditions before birth.

Because minor defects rarely cause symptoms, they may not be discovered until a child is older. Some are found during a routine checkup when your pediatrician hears a heart murmur (a swishing or whooshing sound between heartbeats). While most murmurs are harmless, some can be a sign of a heart problem.

Depending on your baby’s symptoms, your pediatrician may suggest tests such as:

- Electrocardiogram

- Echocardiogram

- Chest X-ray

- CT (computed tomography) scan

- Cardiac MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)

- Diagnostic cardiac catheterization

- Genetic testing

Treating congenital heart defects

Doernbecher offers leading-edge care for all types of congenital heart conditions. Your child’s treatment will depend on the specific diagnosis.

Some mild conditions heal on their own or can be managed with medication. More serious conditions may need surgery in the first year of life.

Children with complex conditions may need additional surgeries and follow-up care, sometimes throughout life.

Treatments your child needs may include:

- Medications to help your child’s heart work efficiently, to prevent blood clots or to control an irregular heartbeat.

- Cardiac catheterization, a method that lets doctors repair some heart conditions without surgery.

- Surgery to close a hole in the heart, repair valves or widen blood vessels.

- An implantable heart device, such as a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) to regulate your child’s heartbeat.

- Heart transplantation in rare cases when a serious heart defect cannot be repaired.

Types of congenital heart defects

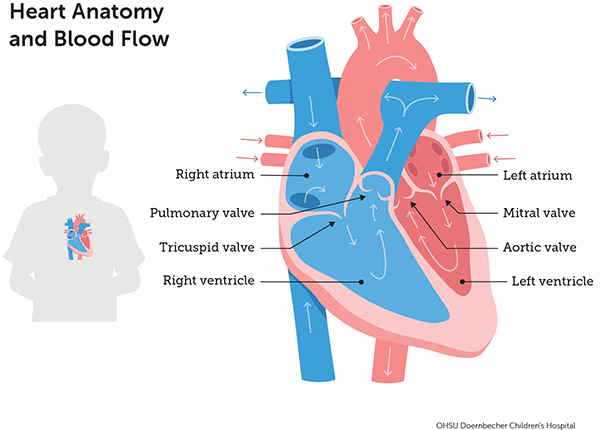

To best understand the following conditions, it might help to review the “How the heart works” section on our Understanding Pediatric Heart Conditions page.

Anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery: The left coronary artery stems from the pulmonary artery instead of the aorta, starving and damaging the heart muscle. It can be corrected with surgery.

Aortic regurgitation: The aortic valve doesn’t shut tightly, allowing blood to leak back into the left ventricle. This can cause the left ventricle to work harder. Mild cases may need only monitoring. Medication or surgery may be recommended in other cases.

Aortic stenosis: In this relatively common condition, the aortic valve is narrowed. This means the left ventricle has to work harder, which can weaken it over time. Children with no symptoms may need only monitoring. For others, doctors may recommend minimally invasive catheterization or surgery.

Atrial septal defect: Babies born with this condition have a hole in the wall that separates the heart’s upper chambers (atria). Over time, it causes the heart to work harder, increasing the risk of heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. Because atrial septal defects often have no symptoms, they can go undetected for years. Catheterization or surgery may be recommended to treat symptoms and prevent future complications.

Atrioventricular septal defect: A large hole in the center of the heart allows blood from all four chambers to mix, causing problems with the heart and lungs. In most cases, the child has surgery before age 2. Atrioventricular septal defects are more common in children with Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome).

Bicuspid aortic valve: Babies with this condition have an aortic valve with two flaps instead of three. The valve may allow blood to leak back into the heart (aortic regurgitation), or the valve can stiffen and narrow (aortic stenosis). Treatment can range from monitoring to surgery.

Coarctation of the aorta: The main artery that delivers blood to the body is narrowed. If left untreated, this condition can cause high blood pressure in the body. It’s treated by widening the narrowed part of the aorta with surgery or catheterization.

Double outlet right ventricle: The heart’s two major arteries both connect to the right ventricle. It is treated with surgery.

Ebstein’s anomaly: This rare condition affects the tricuspid valve — the valve that allows blood to flow between the heart’s right-side chambers. Severe forms are treated with surgery.

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome: In this type of single ventricle heart disease, the left side of the heart is underdeveloped. The aorta, left ventricle and valves are not formed or are too small. After birth, babies usually have three operations over several years to allow the right ventricle to take over for both sides.

Mitral valve prolapse: The mitral valve’s flaps bulge (prolapse) into the left atrium. This condition affects about 2% of the population and runs in families. Certain connective tissue disorders, such as Marfan syndrome, commonly involve the mitral valve.

Mitral valve regurgitation: The mitral valve’s flaps don’t close tightly, causing blood to leak into the left atrium. It may develop slowly as a child grows older. A heart defect or an illness such as rheumatic fever may be the cause. Symptoms can be controlled with medication but sometimes need surgery.

Mitral valve stenosis: The mitral valve, which moves blood through the heart’s two left chambers, is too narrow, causing blood pressure to increase in the upper chamber. This high pressure can back up into the lung arteries. Children with this defect may need only monitoring. In other cases, medication, catheterization or surgery to replace the valve may be recommended.

Partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection: Some of the four veins that bring blood back from the lungs connect to the wrong side of the heart. For example, they may connect to the right atrium instead of the left atrium. Mild cases may need no treatment. In others cases, surgery is needed.

Patent ductus arteriosus: A ductus arteriosus is a channel between the artery that carries blood to the lungs (the pulmonary artery) and the aorta, which carries oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body. All babies are born with this opening (they need it in the womb), but it usually closes on its own. If it doesn’t, blood from the arteries mixes, making the heart and lungs work harder. Treatments include medication, surgery or catheterization.

Patent foramen ovale: All developing babies have a small opening (foramen ovale) in the wall between the heart’s upper chambers (atria). Normally, the tissues grow together and seal the hole shortly after birth. But in about 25% of newborns, the hole stays open. Usually, no treatment is needed. Many children grow to adulthood without knowing they have it. Rarely, the doctor may recommend catheterization to close the hole.

Peripheral pulmonary stenosis: Branches of the arteries that bring blood from the heart to the lungs are narrowed. A child with this condition may need only monitoring. The doctor may recommend catheterization or, in some cases, surgery to open the narrowed branches.

Pulmonary atresia: The pulmonary valve doesn’t form correctly, preventing blood from flowing to the lungs to take up oxygen. Some babies with this defect have a small right ventricle. Treatment soon after birth is often required.

Pulmonary stenosis: The opening of the pulmonary valve, which lets blood move from the heart to the lungs, is narrowed. This forces the heart to work harder to pump blood. Mild forms usually need no treatment. In more serious cases, catheterization can open the valve.

Tetralogy of Fallot: This relatively common combination of heart defects is marked by a hole between the right and left ventricles (ventricular septal defect) and a narrowed passage between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. Together, these conditions reduce blood flow to the lungs and allow oxygen-poor blood to flow into the aorta and the rest of the body. This can cause the baby to have bluish skin. Tetralogy of Fallot is corrected with surgery.

Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: All four of the blood vessels that bring blood back from the lungs (pulmonary veins) connect to the heart in the wrong place. Most babies with this defect have surgery soon after birth.

Transposition of the great arteries: The two main arteries that carry blood out of the heart — the pulmonary artery and the aorta — are switched in position. This causes blood to circulate through the heart and lungs the wrong way. Transposition of the great arteries is typically diagnosed before or shortly after birth. It’s usually repaired within the first weeks of life.

Tricuspid atresia: The tricuspid valve does not form normally and cannot open. In many cases, the right ventricle is extremely small. This condition is treated with surgery.

Truncus arteriosus: Two blood vessels (the pulmonary artery and the aorta) that are normally attached to two separate ventricles are replaced by just one blood vessel attached to both ventricles. This allows oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood to mix, causing the heart to work harder. It is repaired with surgery.

Vascular ring: The baby is born with the aorta or its branches surrounding the windpipe and/or esophagus (throat/food pipe). This may affect breathing and swallowing. Not all patients need treatment, but surgery may be needed to improve symptoms.

Ventricular septal defect: The wall between the heart’s two lower chambers (ventricles) has a hole. Extra blood goes to the lungs, making them work harder. Often, the hole closes on its own. Other times, surgery or, rarely, catheterization may be needed to close it, usually in the baby’s first year of life. Ventricular septal defects are the most common heart defect.

Adult congenital heart disease

Because of treatment advances, most children born with heart defects go on to live normal lives. In the U.S., nearly 1.5 million adults have a congenital heart defect, outnumbering children with heart disease. They still need monitoring, though, because complications can develop later in life.

At Doernbecher, our children’s heart experts work closely with the OHSU Knight Cardiovascular Institute’s adult congenital heart disease program.

For families

Call 503-346-0640 to:

- Request an appointment.

- Seek a second opinion.

- Ask questions.

Locations

Parking is free for patients and their visitors.

Doernbecher Children’s Hospital

700 S.W. Campus Drive

Portland, OR 97239

Map and directions

Find other locations across Oregon and in southwest Washington.

Refer a patient

- Refer your patient to OHSU Doernbecher.

- Call 503-346-0644 to seek provider-to-provider advice.

A partner to patients

Learn how OHSU heart specialist Dr. Abigail Khan helps young adults manage — and thrive — with congenital heart disease.