"There's a Place for You": Oregon Women in the Health Sciences

“There’s a Place for You”: Oregon Women in the Health Sciences centers selected stories of women’s lived experiences in the health professions, juxtaposed with popular images and marketing materials aimed at recruiting women into health sciences careers. Interviews, surveys, letters, and photographs document the pursuit of professional lives devoted to science, healing, and improving the well-being of patients.

Curated by Pamela Pierce, Digital Scholarship and Repository Librarian, OHSU Library. Last updated May 2020.

Early Women Doctors in Oregon

In 1877, eighteen years after Oregon became a state, women began attending school in the Department of Medicine at Salem’s Willamette University. During this time period, settlers living in isolated areas would sometimes have to travel long distances for medical care. Doctors also traveled to see patients using buggies or wagons. A knowledge of general medical practice would also have been essential in this time period.

By attending Willamette University and obtaining their educational in a co-educational environment, graduates were in some ways breaking with tradition. The earliest female attendees of medical school went to institutions entirely devoted to the instruction of women. Obtaining clinical instruction is hospitals was difficult and only economically privileged students could obtain experience in the hospitals of Europe.(1)

In Restoring the Balance: Women Physicians and the Profession of Medicine, 1850-1995, Ellen S. More describes the pressures surrounding the specialization women selected. In 1880, choosing to specialize in obstetrics, gynecology, or pediatrics might have been seen as a sign of “narrowing training” or “incomplete preparation”.(2) Even as the level of prestige given to certain areas of the health sciences changed over time, women still had fewer possibilities. This was partly due to national specialty societies refusing to admit women.

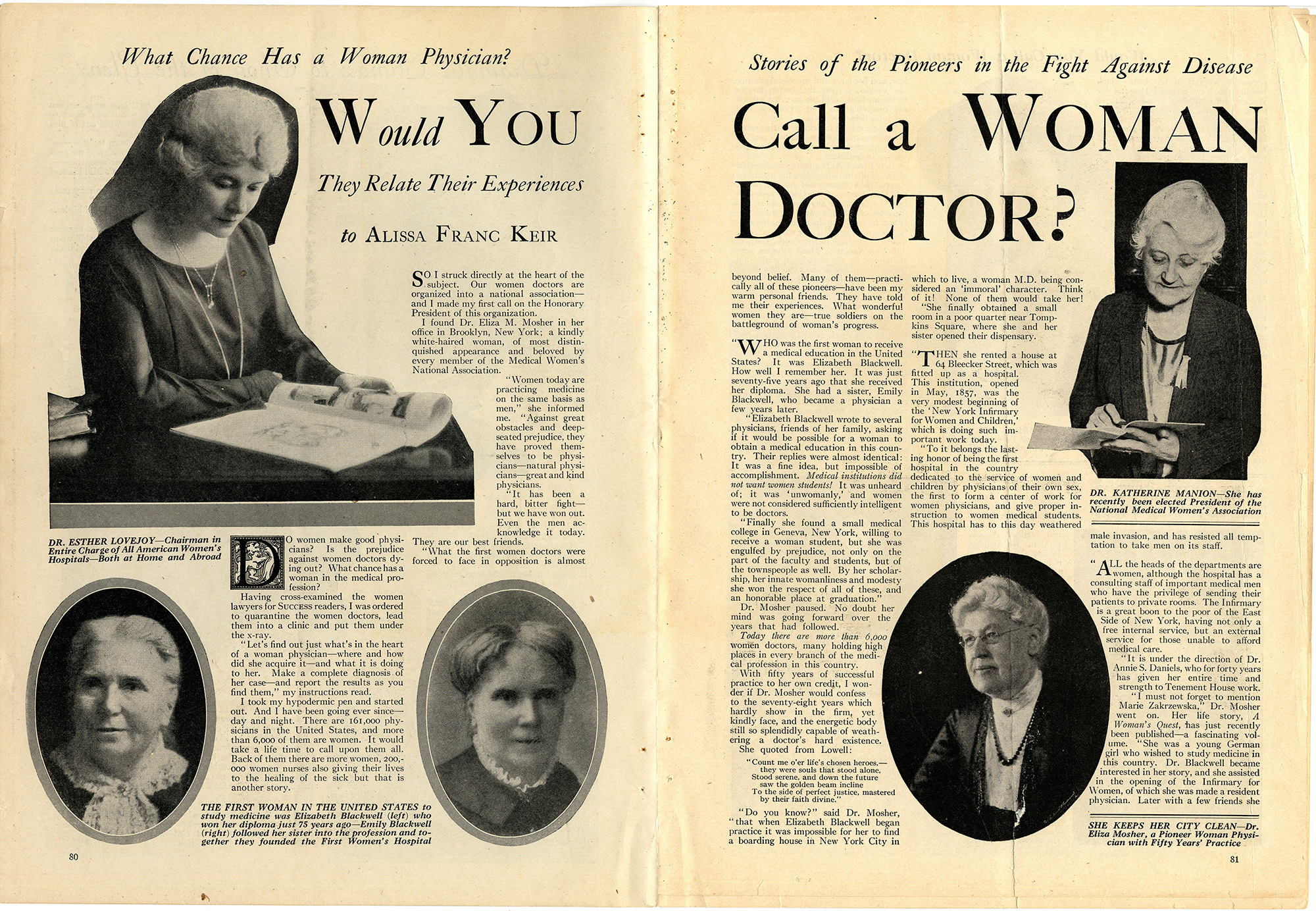

“Do women make good physicians? Is the prejudice against women doctors dying out? What chance has a woman in the medical profession?” Alissa Franc Keir decides to answer those questions by talking to a range of women doctors in this feature in the March 1925 issue of “Success" magazine, founded by American self-help author Orison Swett Marden. One of the physicians interviewed was world-renowned Oregon doctor and School of Medicine alumna, Esther Pohl Lovejoy (M.D., 1894).

The article uses feminine metaphors to describe the clinical work of women doctors; for example, Keir says of Dr. Bertha Van Hoosen, of Chicago, who performs “several major operations per day,” that she “puts into the most difficult piece of surgery the same grace, delicacy and skill as the lady of leisure puts into embroidery.” However, Keir also quoted the interviewed physicians extensively, so that while the description of Dr. Lovejoy employs a reference to her “unusual and romantic” personal history, the article also quotes Lovejoy’s own powerful descriptions of colleagues in the American Women’s Hospitals service: “Dr. Etta Gray is a woman of great executive ability, and a very able surgeon … She was the only surgeon in a large district, and all kinds of major surgery was brought to her.” (Click on image to view full article)

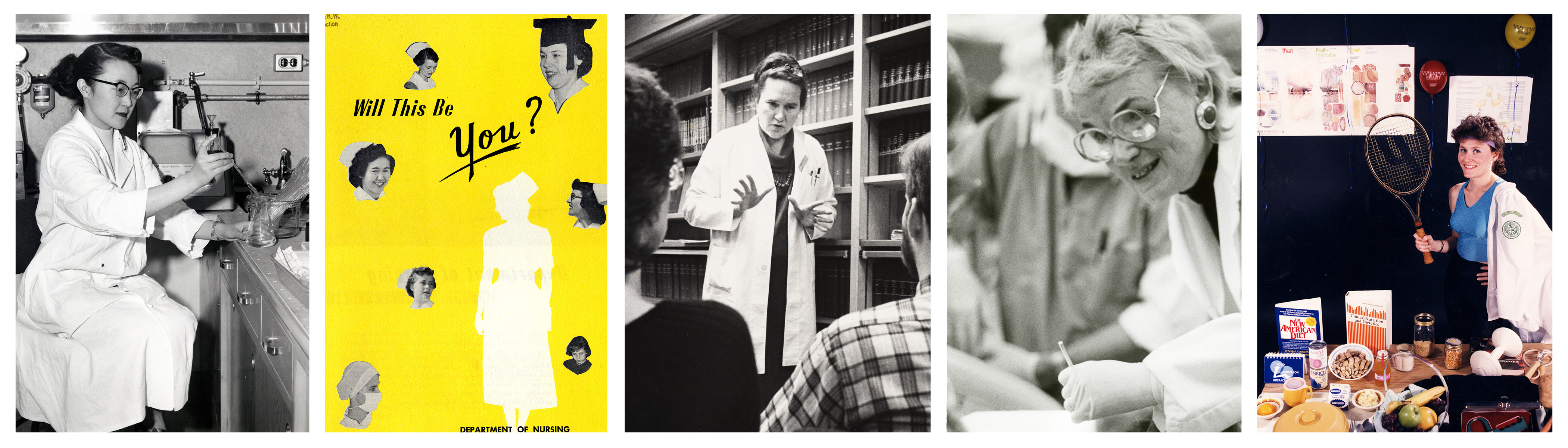

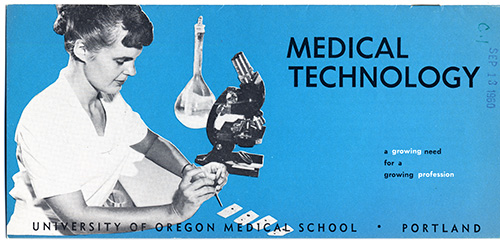

Marketing Nursing and Other Health Science Careers in Oregon

Marketing materials strove to sell women on the health professions, while simultaneously selling the role of women in those professions to the larger health science community. During the 1950s, a brochure selling the nursing profession might include images of nurses working with children and infants while also balancing a family life. Motherhood was never far away. The appeal rested on the excitement of the job, caring for the sick, and teaching people how to keep well. The implicit promise of social fulfillment, love and admiration would follow.

Earlier marketing materials also clarified that young women, single or married, could enter a program. Some of these items also stopped the educational story at commencement, not describing the journey of getting a job or achieving financial independence within the health sciences.

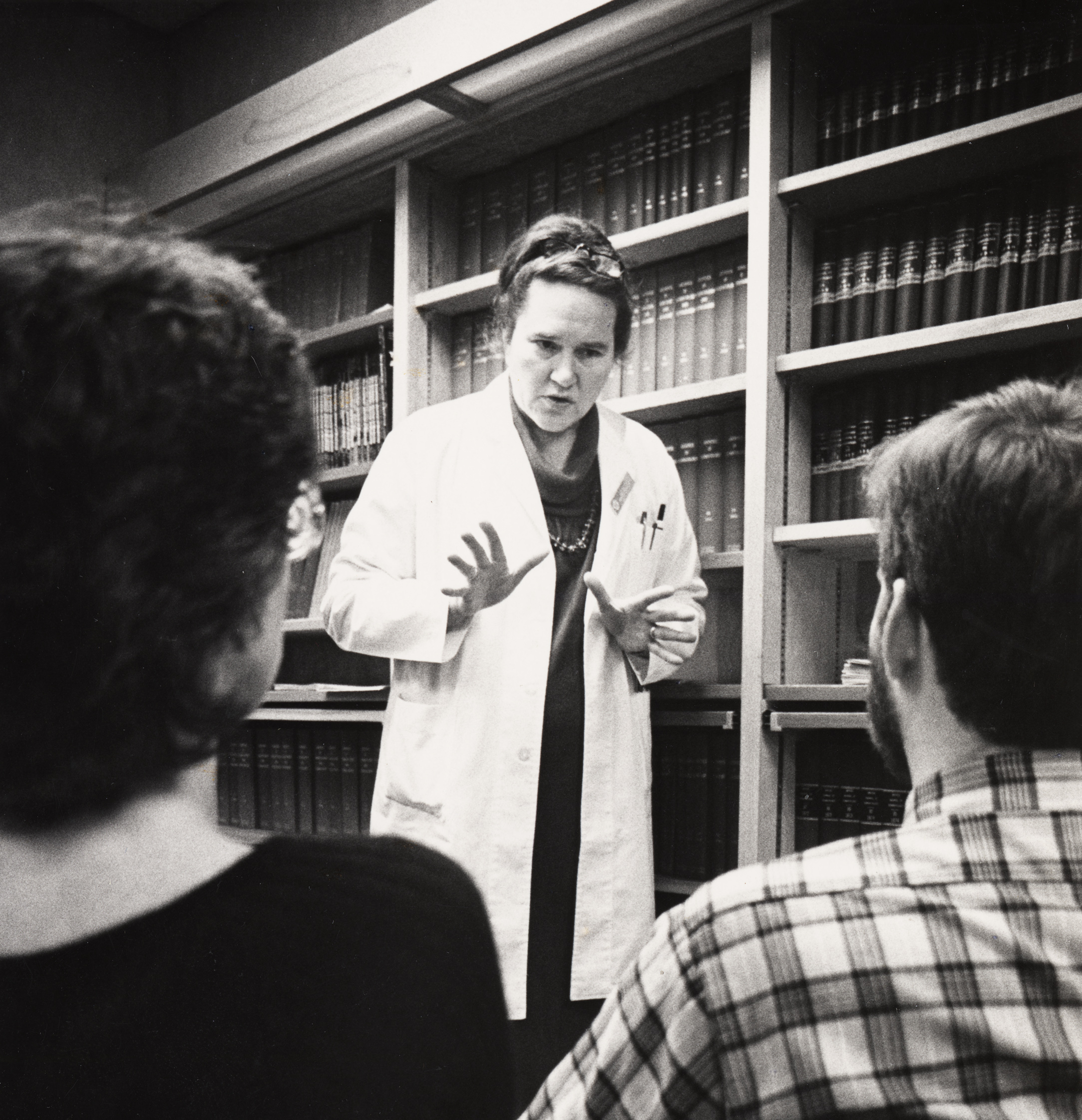

Gradually, advertising shifted to reflect the wider career possibilities and leadership roles women could pursue within the health sciences. Images selected for these materials also include women actively engaged in their daily work. However, women still may have received the best information on the career through lived experience and mentorship from professionals working in the field.

Professional Experiences in the Health Sciences

“Medical school is just a beginning, after four years there is the problem of an internship which is difficult—then more training in your specialty—which all takes time and money, and some physical stamina, but in spite of it all, these six years have been some of the happiest in my life ...” writes Thelma Perozzi about her time attending medical school in Oregon. Perozzi successfully found work at the Children’s Hospital in Iowa City.

Women needed to gain experience through internships in order to be successful on the job market. The Progressive Era’s focus on public health and hygiene opened up additional opportunities for women in medicine, nursing, and other areas of the health sciences. However, change was slow to occur. In his 1936 address at the Alpha Epsilon Iota medical sorority annual meeting, physician William Middleton characterized the reality of the situation for emerging women physicians, noting, “In the medical profession, whether in hospital work or in general practice, a mediocre man can be placed more readily than an unusual woman,” Middleton emphasized to members of the women’s medical organization that “the qualities which we hold as womanly, may be misinterpreted in the physician, since the sympathetic approach may give the impression of faint-heartedness.”

What the optimistic popular images and marketing materials aimed at recruiting women to health professions cannot show is the lived experience of those who chose to follow this path. Primary sources like interviews, surveys, letters, and photographs can document some of the clinical, scholarly, and professional experiences of women in the health sciences.

Women dental professionals continue struggle with dental equipment that is predominantly made for men’s bodies, and advertisements in dental publications continue to target mostly men. One way to gain forward momentum in the profession is for more women to gain leadership roles in professional societies and in academic institutions. Mentorship is also essential. According to Dr. Mary Martin, past president of the American Association of Women Dentists, “The greatest gift women leaders can give to other women is to take them under their wing. My biggest guidance to give young women dentists is that every time you take a step up, turn around and see who you can bring up with you.” (3)

Lucy Davis Phillips and A Study of Women Graduates of the University of Oregon Medical School and Willamette University

Lucy Phillips became Registrar at the University of Oregon Medical School in 1918 and held that position until shortly before her death in 1943. When Phillips started her position, the school was still based in a single Victorian building on Northwest 23rd Avenue and Lovejoy Street. As a registrar, Phillips evaluated and summarized the transcripts of applications for admission to the School.

Phillips also compiled a record of what women did after graduating from medical school. Phillips created A Study of Women Graduates in the form of a scrapbook. Materials included were photographs, biographical information, and obituaries for some individuals. Newspaper articles and other information were added to the volume after Phillips death. A Study of Women Graduates of the University of Oregon Medical School and Willamette University is an essential history of the lived experience of female graduates.

The surveys Phillips conducted as part of her work asked women whether they were married or single, practicing at the present time, their number of years in practice, their specialty, and what advice they would give to a prospective medical student. Gathering this information gave women the opportunity to reflect on the reality of their professional experiences. Phillips did most of her work on A Study in the mid-1930s. In the late 1950s, Betty Friedan survey the Smith College class of 1942 and was inspired to write The Feminine Mystique based on what she discovered. Examining the accomplishments of women can be a catalyst for change.

The Library has digitized this collection of surveys, along with some contextual materials.

Oral Histories

Since 1997, our Oral History Program has conducted interviews with OHSU faculty, staff, students, alumni, and policymakers who have contributed to the history of the University and to health sciences in Oregon.

One aim of the collection is to document the stories of Oregon women in the health sciences, in their own words. See below for a few selected oral history interview excerpts highlighted in this exhibit, or visit our Digital Collections and search by keyword to discover many more stories.

Excerpt from an oral history interview with Ann Beckett, Ph.D., R.N., Professor Emerita, School of Nursing, conducted by Anne Heenan, D.N.P.-P.H.N., F.N.P.-C., on April 17, 2016 for the OHSU Oral History Program:

“[T]here were no nurses in my family. And that was interesting. Because I was influenced by, at least as I trace it back in my mind, I was influenced by a lady that was in our church. And I don’t even know if she ever realized that she had that impression on me. But for whatever reason, she worked in public health nursing.

And I don’t know whether it was programs that she would come, but I had the image of her in my mind wearing the navy blue uniform, and being very stately looking, as I recall. Maybe because I was short, she was tall. But I was impressed with the confidence and all that she had. And that stayed in my mind, although I didn’t decide to become a nurse until I got to college …

When I got into college, and I was reading about the history of nursing, and how it started in New York City and sort of moved west. I was impressed with that. For some reason, working in the community, working in public health, I saw as, I’ve used the term before, as sort of edgy. On the edge of things. And that’s how I felt about that lady … that I was sort of drawn to. I just thought that what she did sounded so, and I didn’t use the term, necessarily, exciting … It was just sort of, you were out there working in the street, in the community … in public health.”

Read the full transcript of Dr. Beckett’s oral history interview

Excerpt from an oral history interview with Toni Eigner-Barry, D.M.D., Professor, School of Dentistry, conducted by Henry Clarke, D.M.D., on May 19, 2016 for the OHSU Oral History Program:

“There was one interesting episode the fall of my freshman year … [T]he dental students had a locker room on the second floor of the dental school where we kept our heavy boxes of instruments that were a short distance from the third-floor lab where we used all of those things for our technical classes ... People didn’t change clothes in that room. It was a place to store your things … [W]e got word that this particular associate dean for clinical affairs thought it was improper that there were women in that locker room … And he gathered us, all seven of us, in his office one noon hour and said, ‘Ladies, I think it’s an impropriety that you’re in the locker room with the men. I’ve had some complaints. And I’m going to move you.’ And we started to say, ‘But look, we don’t want to carry our things two more floors. It’s really not a problem.’ And he said, ‘No. It’s an impropriety.'

At that point, there was a knock on the door. Mike Shannon, president of the sophomore class, entered. And he said, ‘Sir, we male dental students think it’s appropriate that the women have their things with us in the locker room. And in fact, if you move them, we’re going to take all of our instruments and have a sit-out in the hallway.’

And he, you know, dean for clinical affairs kind of pushed himself away from his desk and said, ‘Son, son. Don’t back me to the wall.’

And then, I mean, it was this great moment where you realized the tide had turned. It was a new generation. The men in our class kind of welcomed us as equals. And he was outnumbered. Very smart guy. He said, ‘Ladies, I’m going to think about this. And then I will give you written notice if I want you to move. And if you get this, you should do so, and I don’t want to hear any more about it.’ None of us ever heard another word.”

Read the full transcript of Dr. Eigner-Barry’s oral history interview

Excerpt from an oral history interview with Carol Lindeman, R.N., Ph.D., Dean Emerita of the School of Nursing, conducted by Joan Ash on April 17, 1998 for the OHSU Oral History Program:

“I think if there is a theme that kind of brings all of it together, is the same concern for health care in this country and that to influence its quality you have to take on multiple assignments, if you will. You can’t just be a dean, or you can’t just be a researcher. It seems to me that society calls on you to say, ‘What talents do I have, and where are they needed,’ and if so, to be willing to use them …

I certainly believe that we have an obligation to give to society, and it seemed to me what I was called upon in terms of my life was this area in terms of nursing and health care. So I said yes to more things than I said no to, and it was a major commitment, and yet I also had a lot of support from my family. My kids are—we still talk about some of the things that they remember, and my one son teasing me that I’d write a grant for 50 cents if I thought I could get it.

I’d bring people into the house, people that were working on research projects, and it was a very stimulating environment for them, so that it wasn’t like this is my work and this is my family life; there was the wish to try to integrate it and to make them feel part of what I was doing and so on.

So they have as many fond memories as I do. I remember one of the kids coming home from school one day and saying, ‘Do you know so-and-so’s mother doesn’t work? What would a woman do, home all day?’ They didn’t ever feel deprived or without attention or what they needed, and they just couldn’t imagine that there was any other way of life. So I had a lot of support, and that also made it possible to do things.”

Read the full transcript of Dr. Lindeman’s oral history interview

Excerpt from an oral history interview with Frances Storrs, M.D., Professor Emerita of Dermatology, School of Medicine, conducted by Matthew Simek on October 19, 2007 for the OHSU Oral History Program:

“So I decided not to go into business, I was going to go into medicine. Carleton, in those days, you had to have something like a chem-zoo major, a chemistry-zoology major to go into medicine.

And the head of the department, the biology department, was a very short man, Dr. Thurlow B. Thomas. And he absolutely hated women. And there were two women in the sciences who were going to go into medicine. And he was short; I’m tall. He came up to me when I announced I was going to go into medicine. He was the pre-med advisor, so he had to write the letters and get everybody ready to go to medical school. And he came up to me, even though I’d had all As in all of his classes, and he looked up at me and he said, ‘Frances Judy’—my maiden name was Judy—’Frances Judy, I personally am going to see to it that you do not get into medical school.’

So I then went to another man whom I had befriended and whom I still have contact with named Henry Van Dyke, who taught comparative anatomy … And Dr. Van Dyke said, ‘Don’t worry, Frances. Every time you decide where you want to apply to medical school, I will send a contradictory letter.’

So Dr. Thomas wrote his letter, and then my friend, Dr. Van Dyke, wrote his letter. And I got into every medical school I applied to. And every time I would get in, I would take the letter of acceptance … and throw it on his desk. Say, ‘Have a look at that, Dr. Thomas!’ And then pick it up and walk out.” [laughter]

Read the full transcript of Dr. Storr’s oral history interview

The History Continues

The items in this exhibit represent only selected experiences documented in OHSU’s archival collections. There is much more history than what we are able to present in this single exhibit. Contact us if you are interested in researching additional stories of trailblazing women in your health sciences specialty of interest.

In addition, there are many more stories waiting to be shared, which may not yet have made their way into our permanent collections. If you have materials related to this history that you’d like to add to the archives, or a suggestion for an oral interview subject, contact Steve Duckworth, University Archivist.

Notes

1 Emily Pope, "The practice of medicine by women in the United States," address to the American Social Science Association, September 7, 1881.

2 Ellen S. More, Restoring the Balance: Women Physicians and the Profession of Medicine, 1850-1995 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 54.

3 Dr. Mary Martin, past president of the American Association of Women Dentists, quoted in "Women in dentistry see progress, continued challenges," Kimber Solana, ADA News, January 18, 2016.